Politics & Society

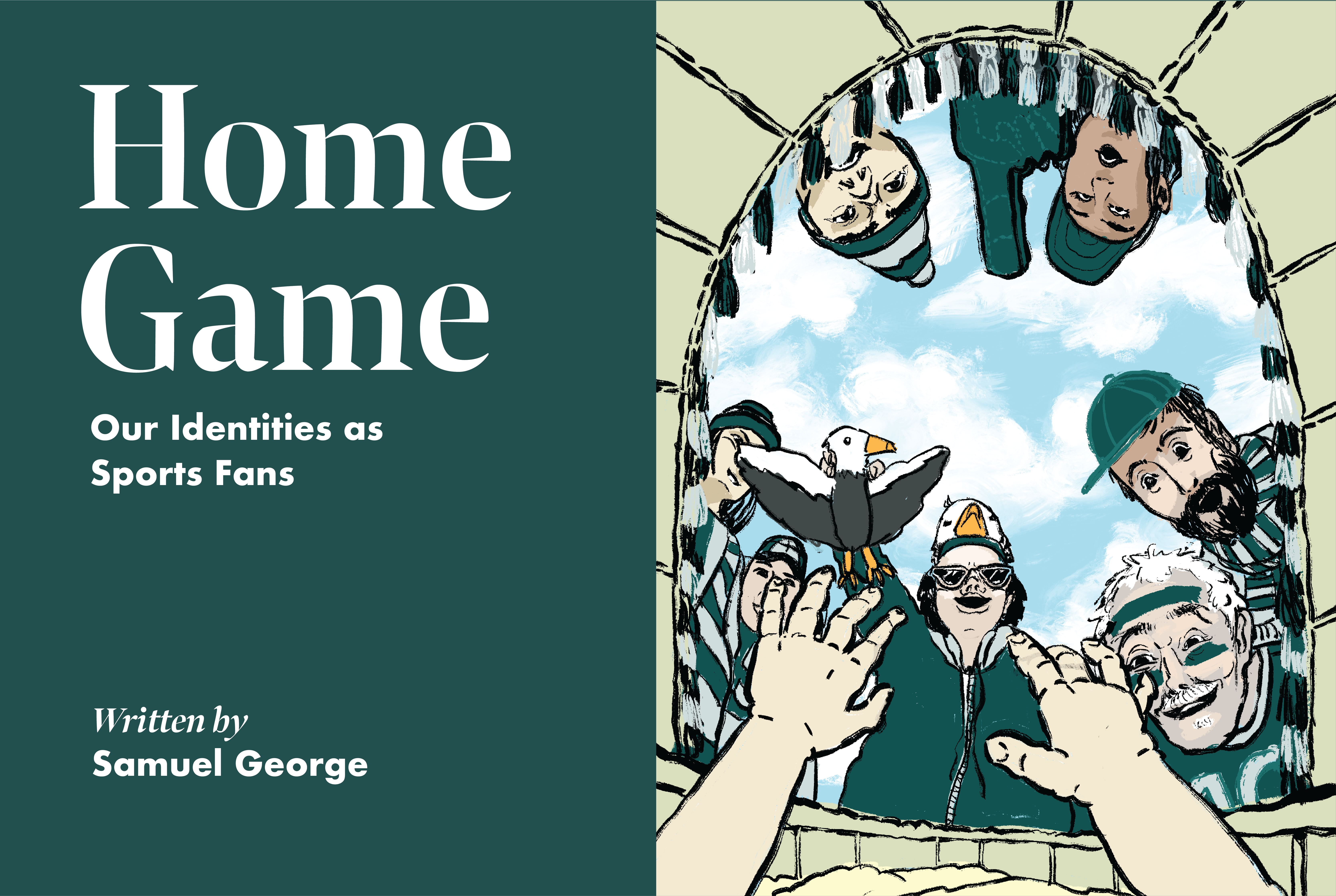

Home Game

Our Identities as Sports Fans

Last October, my father, oldest brother, and youngest brother came to visit me in Washington, DC. This was not normal. In fact, it was the first time they had come to visit all at once, and it would mark the only time we would all be together in 2022.

What monumental occasion reunited our family, which was usually spread across the United States? Alas, we gathered not for the inauguration of a President, nor was it for a solemn visit to one of Washington’s war memorials. We had come together to go see the Philadelphia Eagles, our family football team.

As we filed into the stadium, each in our matching green football jerseys, I realized that somewhere along the line, supporting Philadelphia’s professional sports teams had become a cornerstone of our identity. After all, are there any other causes to which we would pledge our allegiance so publicly?

For nearly four decades, I have ridden the roller coaster of Philadelphia fandom. It’s an emotional investment, and one that takes its toll. As a child, tears would stream from my eyes following a loss, as my befuddled mother desperately tried to rationalize the situation by explaining that none of the players were, in fact, from Philadelphia.

Decades later, the tears may be fewer, but the feelings remain. Recently, as the Philadelphia 76ers choked away a 26-point playoff lead, I found myself on hands and knees, banging my head against the wooden floor, much to the sheer incomprehension of my wife.

In other words, for some reason, we care. Too much? Perhaps. Are we alone? Not by a long shot.

The economic footprint of professional sports reveals just how deeply the games are ingrained in communities on both sides of the Atlantic. The four major U.S. professional leagues generate over $40 billion in annual revenue. The overall economic impact is likely at least double that. The Super Bowl is America’s second biggest food day of the year, after Thanksgiving. In Europe, the top 20 grossing football clubs net over €9 billion in annual income, surpassing the GDP of roughly 60 countries.

For millions around the globe, our allegiance to teams has become a fundamental aspect of who we are, how we present ourselves, and how we gather with friends and family. It is an element of our identity that we share proudly, branded onto shirts, hats, coffee mugs and more.

But what does it mean? As I looked around Washington’s decrepit stadium that afternoon last fall, I saw tens of thousands of other people decked out in our team’s silver and green. I wondered what I had in common with these other Eagles fans? I knew nothing about them. And yet, there I was, whooping and hollering among thousands of others who apparently share this core characteristic.

As a child, my father helped me up to the cheap seats for big games. Now, 30 years later, he leans on me to climb those same stadium steps.

It's a Family Affair

Part of the power of sports is that we often become aware of our sports teams in the years that we slowly become aware of ourselves. For many, this fandom is ingrained from early childhood, as a learned practice from those we love most. A 2011 Murray State University study found that 44% of men and 34% of women cite their parents as the biggest factor in their fandom. This number increases to nearly 61% for men and 42.5% for women when expanded to include grandparents and siblings.

The study underscores the specific influence of fathers on sports fandom: both men and women overwhelmingly cite their dads as “the greatest single influence” in their selection of teams. It’s a deeply embedded relationship that changes over the years. As a child, my father helped me up to the cheap seats for big games. Now, 30 years later, he leans on me to climb those same stadium steps.

Outside of immediate family, the only other factors that significantly register in the study are friends (10% for men, 7% for women) and school (8% for men, nearly 15% for women). In other words, if the connection to sports teams is not born in the living room, it is on the playground.

Perhaps this is why, even as we move on from our childhood homes, towns and cities, many of us hold on to those original bonds. Megan Long, Bertelsmann Foundation’s Project Coordinator, grew up in New Jersey, in a family of die-hard Mets and Jets fans. She left in 2009, but her fandom remains. “My team spirit has a lot to do with my family,” she tells me. “It got stronger because it was a familiar comfort, especially when I used to get homesick.”

The further we get from home, the stronger the bonds can become. The games become a shortcut to a time and place that may not exist anymore. We lost my mother in 2016. But when I watch the Eagles, I can still sense her sitting in her blue armchair across from the TV, knitting, and muttering under her breath when one of our loud cheers made her miss a stitch.

This powerful mixture of home, family, youthful joy, and civic pride hooks us from a young age, and becomes a cornerstone of how we understand ourselves. Anthony Silberfeld, our Director of Transatlantic Relations, has lived in Washington, DC for 25 years, yet he remains a big Los Angeles Lakers fan. As he explains it, “Nothing ever brought my family together like watching a Laker victory.” Despite leaving Los Angeles at the age of 17, Anthony believes “the Lakers are as much a part of who I am today as any other influence that came into my life along the way.”

A Global Phenomenon

There are similarities across the pond in Europe. On game day, Germans from throughout the North Rhine-Westphalia industrial belt stream from mid-size towns onto trains in a swarm of yellow and black, on their way to Signal Iduna Park to support Borussia Dortmund. Similar scenes play out in Naples, Liverpool, and Sevilla: where teams are tightly bound to the identity of their hometown.

However, as it is more common in Europe for a city or region to have multiple teams, a fan’s allegiance can reveal a deeper identifying clue. For example, Tottenham Hotspur has long drawn support from London’s Jewish community. The nickname “Yids” serves both as point of pride for some supporters, and a term of antisemitic abuse from the team’s antagonizers. Crosstown rivals Chelsea, meanwhile, manage to appeal simultaneously and separately to both a posh and loutish fanbase.

Bologna’s soccer team has a left-wing reputation, stemming from the city’s communist inclinations in post-war Italy. Famously, the “El Clásico” match between longtime rivals Real Madrid and FC Barcelona has extensive historical and political connotations, rooted in the violence of the Spanish Civil War, the tension between a centralized Spain and the autonomous regions, the legacy of dictatorship, and other deep-seated grudges.

Sometimes, the signaling associated with support tells us more about how someone sees themselves, as opposed to who they actually are. For example, the two powerhouses of Argentine football in Buenos Aires, River Plate and Boca Juniors. By reputation, River Plate is the team for the wealthy, playing in the upscale Nunez neighborhood and nicknamed Los Millonarios. By contrast, their archrivals, Boca Juniors, play in a worn-down port neighborhood, and the club’s supporters cherish its scrappy, working-class immigrant reputation. Nevertheless, plenty of rich people root for Boca, and plenty of working-class folks cheer for River.

Given the global nature of soccer, in which the top teams inevitably field an international starting eleven, there is an additional layer of identification based on nationality and pan-ethnicity. For 15 years, Lionel Messi’s European matches have been must-see TV not only for Argentines, but for large swaths of Latin Americans that find meaning in one of their own succeeding so spectacularly on a global stage. This effect has created no small number of Barcelona fans who rather suddenly became Paris Saint-Germain fans after Messi’s transition from the former to the latter.

These additional identifying characteristics are less extensive for teams in the United States. People don’t support the Cincinnati Bengals for political reasons. They don’t support the Texas Rangers as a demand for political autonomy. My family doesn’t support the Philadelphia Phillies for religious reasons (though that has not stopped us from resorting to prayer).

In fact, in a divided, politicized, and economically stratified society, sports seem like one of the few elements of American life where support doesn’t fall along these lines. Both Democratic President Joe Biden and arch-conservative Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito are Phillies fans, and both attended the same Phillies World Series games in fall of 2022. What a shame they could neither veto nor overrule their team’s loss.

Are we alone? Not by a long shot.

The Identity of a City

Sports can act as a powerful unifier. As Anthony Silberfeld, our resident Lakers fan explains, fandom isn’t just about family—nothing brings his city together like a good Lakers team. This is certainly the case in Philadelphia. Playoff season in Philly can resemble holiday seasons in other parts of the world. The city is full of public decorations, festive outfits, and friendly banter on the streets, in trains, and office elevators. “Go Birds” becomes a substitute for “Hello”. Family gatherings are planned to coincide with the games. And a big win can lift the spirits of the city for weeks. My father, who worked decades as a public defender in Philadelphia, remains convinced that juries and judges are more forgiving on Mondays after an Eagles win.

Another factor is that Philadelphia fans have routinely suffered exquisite disappointment. The Phillies, a franchise dating back to 1880, have won baseball’s championship precisely twice, racking up over 11,000 losses along the way. The Eagles, the city’s crown jewel, won the Super Bowl for the first time only in 2018. The last time the 76ers won, Ronald Reagan was president. When the Flyers last won, it was Gerald Ford. Every other season has ended in disappointment, usually of the soul-crushing variety. In a recent blow for the city, both the Phillies and Eagles lost their respective championships in a three-month span bridging 2022 and 2023.

Following a big defeat, the city goes silent for days. The decorations come down. The jerseys and costumes come off. In classrooms, trains, and elevators, folks gaze at their feet, growling to themselves about what might have been. Juries and judges may be less forgiving.

But then, somehow, in a process that defies logic or expectation, the city regroups within a few months. Hope springs eternal. Philadelphia is back, and ready for more. Louder than ever before. In part, the boisterous attitude stems from the knowledge that it will almost certainly end in agonizing defeat. We might as well scream a little while we can. Every carnival has its end, but every end has its carnival.

And I probably won’t be there to see it in person: after all, I left Philadelphia 15 years ago. But I will be watching it on TV. For a split second it will take me back to the top of Veterans Stadium, where I sat next to my father as an eight-year old, feeling the 70,000-seat stadium shake in rapture for a Phillies World Series game. It will take me back to my mom in her powder blue armchair. And even if I promise my wife I will behave, win or lose, we both know that’s not true. I can’t help it. It’s who I am.