Digital World

Our Post Pandemic Future of Work Part 2 of 2

Policy Approaches for a Contested World

To many, the future of work is a question of technology and its impact on jobs, workers, the economy, and work itself. This way of looking at it has resulted in policy solutions focusing on workers and what they can do to prepare for the inevitability of technological disruption.

But future-of-work solutions will not be devised in a vacuum, and technologies being developed and deployed today will also affect citizens’ trust in leaders and institutions, which will in turn impact policymakers’ ability to craft sustainable solutions.

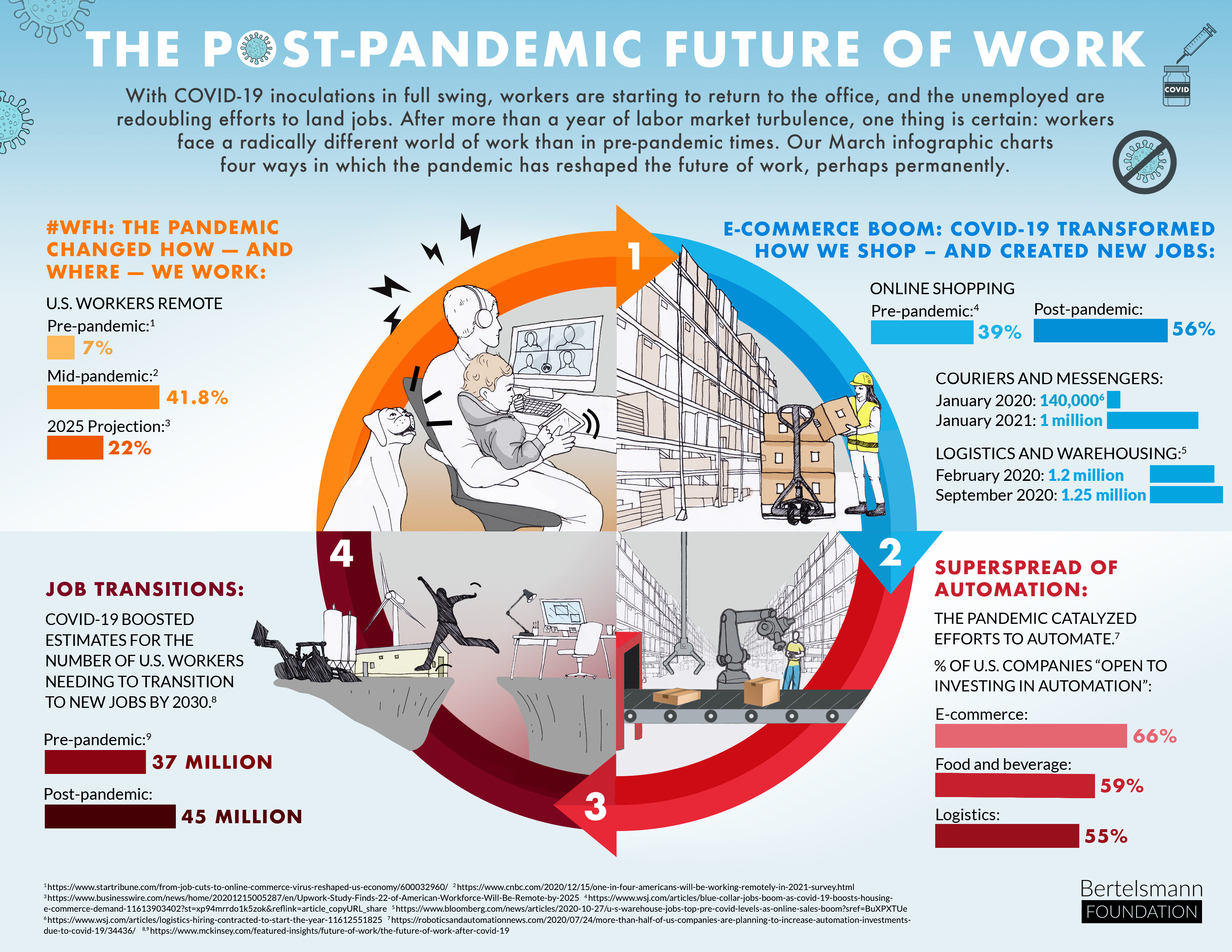

This series of B|Briefs assesses the state of the future-of-work debate and provides suggestions for where to take the conversation next. Part 1 outlines ways in which COVID-19 has changed the future of work. This B|Brief (Part 2) discusses how the future-of work-debate will need to transform if it is to bear fruit over the coming decades.

The Future of Work in 2040

In its most recent foresight report, Global Trends 2040, the U.S. National Intelligence Council (NIC) highlights new technologies’ role in stoking global competition over the coming decades. The council predicts that new technologies will unlock novel solutions to megachallenges “such as aging, climate change, and low productivity growth,” while fueling “new tensions and disruptions within and between societies, industries, and states.”

The report outlines a stark dilemma for policymakers: As external disruptors such as environment and technology drive evermore-complex demands for policy solutions, citizens grow increasingly disaffected with their leaders and institutions, who cannot generate policies to cope with “disruptive economic, technological, and demographic trends.”

This, in turn, leads citizens to recoil from external disruptors by focusing on what they can control: their internal core identity and finding common cause with like-minded groups. Thus, new technologies with the promise to make the world “more open and connected” are being released into an environment that is increasingly hostile to the (broadly defined) concept of connectivity itself.

Thus, new technologies with the promise to make the world “more open and connected” are being released into an environment that is increasingly hostile to the (broadly defined) concept of connectivity itself.

This glaring paradox limits the transformative potential of new technologies, no matter their mass appeal. And resolving this paradox is key to developing policy around new technologies and the future of work.

Bending the Future of Work to Us

At its core, the future-of-work conundrum is about the existential threat (or promise) posed by new technologies to work, workers, and the workforce. Thus far, the debate and resulting policy solutions — including coding bootcamps, worker reskilling and retraining, modernizing social support systems, STEM education, and even the golden goose of universal basic income — have focused on shaping workers and industries to the writ of these new technologies. Workers must prepare for inevitable disruption brought by new technologies.

But what happens when our ability to generate “good” future-of-work policy is sapped by exogenous technological forces, and our leaders can no longer find durable solutions? For now, our ability to craft decent policy is predicated on continued trust in our leaders and institutions to shepherd us in the right direction.

But what happens when our ability to generate “good” future-of-work policy is sapped by exogenous technological forces, and our leaders can no longer find durable solutions?

But the future of work is not immune from the downward spiral of trust outlined by the NIC: As new technologies are rolled out, citizens will demand policy solutions that not only guide their technical deployment, but also guarantee jobs and incomes. Therefore, in the future, the deployment of new technologies will put strain not just on workers and industries, but also on leaders and the policymaking process itself.

Employers and politicians cannot continue foisting the burden of preparing for the future of work onto workers indefinitely. That approach will provide diminishing returns over the coming decades as workers demand more from technologies — and the policymaking process itself. In order to cope, we will need to bend the future of work to these new realities.

The Post-COVID-19 Future of Work

The COVID-19 pandemic illustrates policymakers’ inability to forge good policy in a time of crisis. Although much has been made of the liberating impact of 10-year-old technologies such as Zoom, as we exit the pandemic, we are reverting to a laundry list of pre-pandemic solutions such as retraining, upskilling, and lifelong learning.

Dumping the burden of responsibility for technological change onto workers will do little to pave the way for the implementation of new technologies, and will do nothing to overcome citizens’ growing distrust of their leaders.

Post-pandemic, it would be a mistake to reenter into a binary discussion of whether technology and automation will create or destroy jobs. The pandemic and the NIC report suggest that we have, in essence, been asking (and solving for) the wrong questions.

Dumping the burden of responsibility for technological change onto workers will do little to pave the way for the implementation of new technologies, and will do nothing to overcome citizens’ growing distrust of their leaders.

So, What Is to Be Done?

In its report, the NIC dryly notes that countries “focusing their resources today are likely to be the technology leaders of 2040.” To the NIC, “resources” run the gamut from manufacturing, education, and funding to the workforce and the policymaking process itself. Drawing on key lessons gleaned through the foundation’s future-of-work project streams, three approaches can arrest the downward spiral forecast by the NIC.

First, we should ingrain future-of-work planning in technology policy. In its report, the NIC states that many technologies have moved from the realm of theory and research to real-world application, with all its consequences. From quantum computing and various applications of AI, researchers, developers, and companies have fanned hopes for the life-altering transformation these technologies will deliver.

But marketing and lofty promises will do little to allay mounting public angst over new technologies and their impact on the world of work. Increasingly, companies will need to have not only a plan for the ethical development and deployment of new technologies, but also proof that the new technologies will create jobs and economic opportunities for citizens.

Companies will need to have not only a plan for the ethical development and deployment of new technologies, but also proof that the new technologies will create jobs and economic opportunities for citizens.

Second, policymakers will have to become proficient at leading, developing, and implementing future-of-work policymaking at the city, county, and state level. Although unemployed workers benefited from direct assistance provided by the CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan Act, states and regions were largely left to their own devices to determine locally relevant policy responses.

COVID-19 created new regional inequalities by torching low-wage positions in regions overly dependent on tourism, hospitality, and logistics and warehousing. Many of these jobs had been considered highly vulnerable to technology and automation before COVID-19, but the pandemic outdid even the gloomiest predictions. Three U.S. future-of-work case studies completed by the foundation were particularly hard hit, with unemployment spiking to record levels in Las Vegas, Orlando, and Riverside.

Post-pandemic, local leaders and governors are grappling with job quality, automation potential, and economic diversification. For example, having seen COVID-19 lay waste to jobs and the economy, Gov. Steve Sisolak of Nevada recently threw his support behind “innovation zones” and a Blockchain-based city in a play to diversity the state’s economy beyond tourism and hospitality.

Third, it is clear that the proliferation of new technologies poses challenges not only to workers and the world of work, but also to policymaking and governance. New technologies will place new demands on institutions and policymakers, but their ability to respond in a meaningful way will also be more constrained. Bridging the widening gaps between new technologies, citizens’ demands, and policymaking capacity will be key to pulling out of the downward spiral of trust outlined in the NIC report.

New technologies will place new demands on institutions and policymakers, but their ability to respond in a meaningful way will also be more constrained.

So how can this difficult feat be pulled off? One way is to repair the feedback loop between policymakers and citizens through systematic stakeholder engagement and by solving the right questions for the right groups of people. Fostering this cycle is not just an exercise in corporate social responsibility; it will be key to maintaining national and international competitiveness going forward. Upfront investments in policymaking capacity today will help us resolve current challenges and will be a down payment on future challenges that have not yet come into view.

The World in 2040

The NIC forecasts a world in 2040 in which the battle lines are entirely different than the ones we live with today. External forces such as technology will be at the center of this contestation, with power and influence stemming not just from who controls the commanding heights of new technologies and their deployment, but with how we deal with with their social, political, and economic ramifications. Benefiting from new technologies rests as much on ‘good’ policymaking as it does on the technologies themselves.

It is clear that we are in the very early days of creating policy around new technologies. Will today’s democratic systems with robust policymaking apparatuses smooth out the wrinkles caused by new technologies? Or will we be forced into a tailspin where new technologies instead fan distrust among citizens, institutions, and of the technologies themselves?

Making investments in technology policymaking and the future of work ensures that we can contest in 2040 – and beyond.