Digital World

Our Post-Pandemic Future of Work Part 1 of 2

Making Sense of the Debate

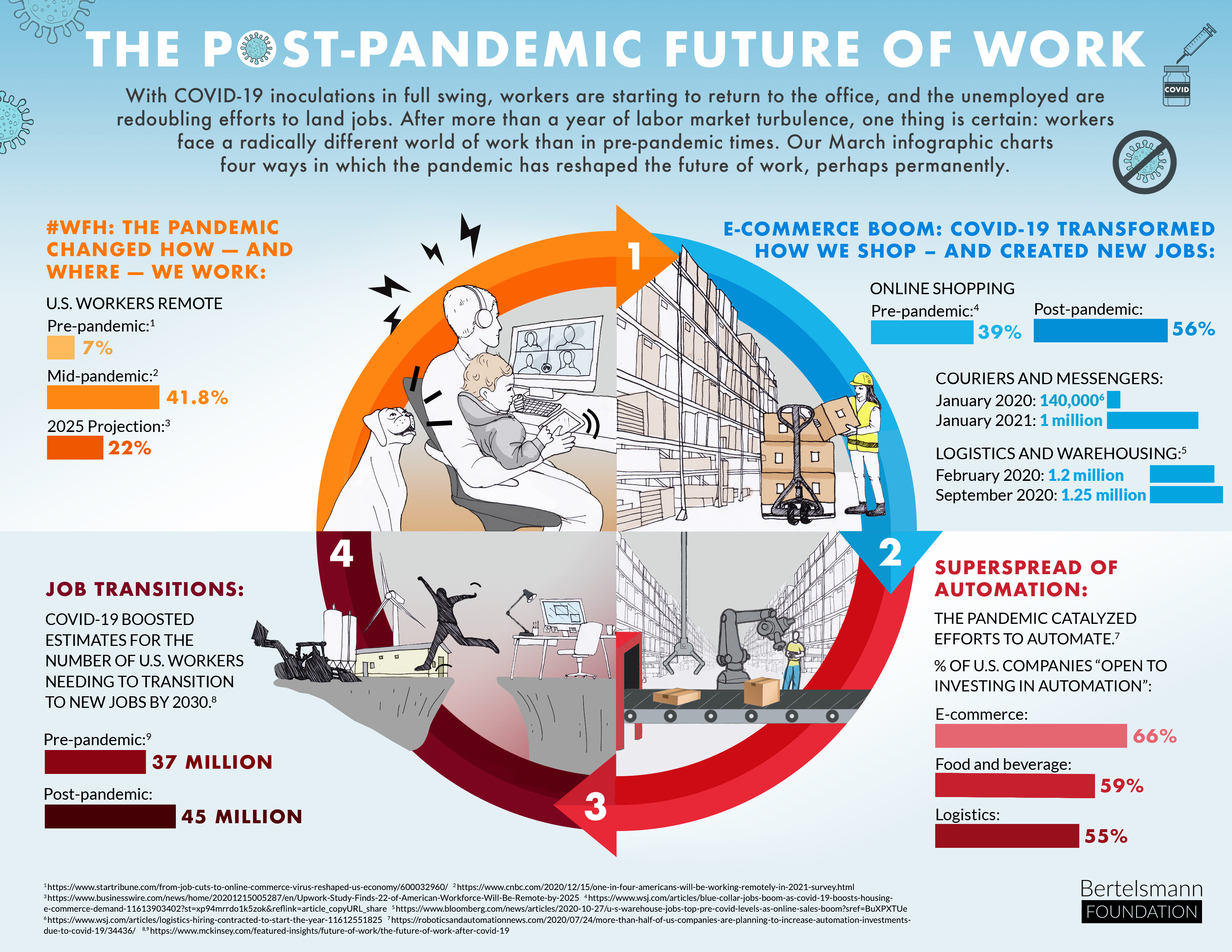

More than a year has elapsed since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. The news presaged a public health crisis that generated massive unemployment and upended the world of work as we know it. As the pandemic metastasized, it forced workers, employers, and policymakers into an unplanned future of work trial that many — at least in pre-pandemic times — had envisioned unfolding at a measured pace over decades.

Thankfully, a large-scale vaccination drive will soon bring back some version of normal. Students will return to classrooms, airports will buzz with passengers, and workers will fire up their desktop computers and plop back down into their annoyingly stiff office chairs. But as the menace of COVID-19 recedes, it will leave an indelible mark on the world of work.

Given the pandemic’s profound impact on jobs, tasks, offices, and the future of work debate, the time for reflection has arrived. This two-part series focuses on how COVID-19 has impacted the future of work and where we go from here. Part I discusses ways in which COVID-19 has altered the future of work. Part II (forthcoming) highlights policy approaches for decision-makers as they navigate the post-COVID-19 recovery.

The Problematic Future of Work Hype Cycle

From the start, the future of work debate has been fueled by a combination of technological development and hyperbolic media coverage. Pre-pandemic, the hype cycle fed on existential concern over rapid advances in technology and automation, which seemed to threaten the value of human labor itself.

The tension between new technologies ostensibly developed to solve humanity’s problems, on the one hand, and their ability to simultaneously diminish the value of human agency, on the other, spawned a fascinating public policy conundrum. Constituencies rushed to declare their readiness for the future of work, whatever it meant.

The wild card of the pandemic showcased the haplessness of technology in tamping down a public health crisis and in mitigating the ensuing economic and jobs collapse. It also exposed just how few organizations, policymakers, and workers are, in fact, ready for the future of work.

The wild card of the pandemic showcased the haplessness of technology in tamping down a public health crisis and in mitigating the ensuing economic and jobs collapse.

In stark contrast to the orderly transition that had been envisioned pre-pandemic, employers shed legions of workers as policymakers fumbled awkwardly for solutions. Those still employed lived their own personal future of work experiments, juggling child care, teaching, and conference calls from spare bedrooms. For most, the future of work was not what it was cracked up to be.

The rapid rollout of COVID-19 inoculations has ushered in a fresh hype cycle around the future of work. Technology companies pump out a steady stream of surveys showing contentment with remote work. Privacy advocates sound the alarm over the implementation of new AI surveillance tools in the post-pandemic workplace. Researchers debate how COVID-19 has impacted women’s ability to participate in the labor market. And others push for assistance to retrain workers laid off over the past year.

Pressing beyond these estimates and warnings, the pandemic also revealed some simple future of work truths that will remain constant in the post-pandemic world. Grappling with these challenges is key to developing post-pandemic future of work solutions.

Low Wage, High Vulnerability

Pre-pandemic, the U.S. had roughly 53 million low-wage workers (44 percent of the workforce), many doing customer-facing, “high touch” work in tourism, hospitality, brick-and-mortar retail, and medical services. Despite warnings that these jobs would be vulnerable to technology and automation, they emerged as the default drivers of employment in many parts of the United States.

Unsurprisingly, the pandemic led to steep job losses in these industries, with unemployment spiking to 21.2 percent among workers with a high school education or less in April 2020. This should not have come as a surprise: In recessions dating back to the 1980s, 88 percent of job loss has been concentrated in jobs involving a high degree of repetitive tasks.

Job growth at any cost, even when it comes with a minimum wage of $15 an hour, would do little to improve job quality or head off vulnerability posed by automation.

Despite the rush to restore normalcy in the wake of COVID-19, we should not welcome a return to the status quo of low-wage-fueled job growth. Job growth at any cost, even when it comes with a minimum wage of $15 an hour, would do little to improve job quality or head off vulnerability posed by automation. Estimates show that the pandemic boosted the number of U.S. workers needing to switch to entirely new occupations by 2030, to 14.9 million. Finding ways to equip low-wage workers with automation-resilient opportunities is more difficult than rushing a return to business as usual, but it should be a priority.

Hybrid Work is Not A Panacea

The future of work hype cycle has fueled anticipation of a post-pandemic return to “hybrid” work, in which workers divide their time between the office and working from home, with virtual interaction picking up the slack. While surveys show that employers believe that remote work has been successful, only 23 percent of workers with less than a four-year degree say their work can be done from home. That stands in stark contrast to the 58 percent of workers with a bachelor’s degree who say their work can mostly be done from home.

The emerging class divide created by the transition to hybrid work threatens the development of sustainable future of work policy for those who need it the most: workers engaged in low-wage work involving many potentially automatable tasks.

Many technology companies have sought to capture the commanding heights of the future of work debate by portraying hybrid work as a force that can be unlocked only by using their propriety tools. But these companies may soon be responsible for automating the tasks and jobs of workers who have thus far been unable to benefit from the concept of hybrid work they are championing. Evangelism around hybrid work masks the need to develop future of work solutions for those who do not benefit from the shift to hybrid work.

Building the Debate Back Better

As we emerge from the pandemic, all workers confront a radically different world of work than in pre-pandemic times. But not all workers confront the same future of work reality. While the pandemic piqued public interest in the future of work as a topic, we largely stood by flatfooted as the economic and jobs ramifications of the pandemic washed over us. More broadly, the pandemic showed how ill-equipped we are to deal with more protracted impacts of technology, automation, or the next pandemic.

Even before the pandemic, years of debate over the future of work generated few durable policy solutions, with universal basic income and “retraining” becoming the be-all and end-all of policy options on tap. The lack of durable solutions is partly down to the unrealistic expectations created by the future of work hype cycle. But we have also been left with few good polices because we fixated on crafting policy solutions for the most vocal, rather than the most vulnerable.

More broadly, the pandemic showed how ill-equipped we are to deal with more protracted impacts of technology, automation, or the next pandemic.

The pandemic provides the perfect excuse for workers, organizations, and policymakers to think intentionally about the type of post-pandeic recovery they want. While it will be easy to allow workers to return to positions that will continue to face disruption from technology and automation, the pandemic shows that we need to be intentional about the tasks and jobs that public policy supports.

Stay tuned for Part II in this series covering future of work policy approaches post-COVID-19.