Digital World

The US-German Economic Relationship

Trends in bilateral trade and investment

I. Good Friends in a Dangerous World?

According to the realist school of thought, the world is a brutal, dangerous arena. It is anarchical. No government of governments enforces rules. The motives of other countries are unpredictable, and the threats they pose are potentially existential. In such an environment, one country cannot afford to depend on another. Any cooperation should be understood as ephemeral, lasting only as long as specific interests coincide.

Liberal institutionalists counter that the world need not be that way. They note that mechanisms exist to allow partners to build trusting relationships, to overcome prisoner dilemmas, and to eliminate informational asymmetries that prevent cooperation.

Over the last 75 years, the United States and Western Europe have developed a series of collaborative institutions, norms and political economic regimes that suggest the lofty goals of liberal institutionalism are attainable. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the collective defense alliance, represents an oft-cited, codified, military example. Meanwhile, a shared trans-Atlantic dedication to democracy is demonstrated in an alignment of norms and conceptions of inalienable human rights.

The economic relationship between the US and the EU also underscores the critical ties that bind the two regions. Both share the world’s largest bilateral trade and investment relationship, and they have developed deeply intertwined economies.[^1]Together, they wield significant power over global trade rules, which allows them to increase regulation of labor and health standards, and intellectual property rights.

Yet across the trans-Atlantic community, a populist backlash has emerged against precisely this world order with its notions of free trade, integration and inclusive democracy. Frustrations with liberal institutions fueled the successful 2016 Brexit campaign and propelled Donald Trump’s successful US presidential campaign later that year. Resentment has also given rise to powerful illiberal voices in Austria, Hungary and Italy, and has reinvigorated a dormant German far right.

In the US, one characteristic of the broader rejection of the global system has been a re-evaluation of relationships with traditional allies. President Trump views his country’s relationship with the EU with a jaundiced eye, and with a particular suspicion of America’s core partner in the region, Germany.

President Trump’s antagonism towards Germany is a surprise for many. For decades, Washington’s strong relationship with Berlin (or Bonn) was a bedrock of the broader US-EU relationship. While the Trump administration has not detailed its grievances, the catchphrases and tweets that the president offers typically invoke Germany’s failure to meet non-binding financial targets set by NATO and the supposed fleecing of the US in international trade.

Meanwhile, a stunned Germany faces the prospect of American abandonment of the very global order that Washington built, and of losing the support of a quasi-paternal ally.[2]

This paper focuses on the pair’s economic ties. The goal is to underscore the importance of the relationship to both sides while considering the Trump administration’s objections.

The piece begins with an analysis of German–American trade, the central element of a lopsided bilateral economic relationship that earns the US a sizeable deficit. The paper proceeds to investigate the root causes of that imbalance, beginning with Trump administration claims of an undervalued euro and discrepancies in tariffs. This paper finds that neither offers a persuasive explanation for the German trade surplus with the US[.3]

Instead, the paper argues that German manufacturing competitiveness, and its ability to satisfy niche industrial and luxury markets, sustains heavy demand for German exports (not just in the US, but around the world), while high levels of German savings, combined with domestic underinvestment, curtails German demand for imports, including those from the US.

The essay then considers the importance of foreign direct investment, an area that benefits the US. It concludes by examining how global trends towards economic nationalism could reorient the relationship as both sides may become more inward-looking at the expense of external economic ties.

Such an outcome would be unfortunate. In a brutal, dangerous world, a trusted friend is hard to find.

II. German–US Trade: An Overview

The US and Germany, countries with massive economies, are also major trading partners. This much is indisputable. The extent to which that relationship is mutually beneficial, however, has been the subject of increased speculation under the Trump administration.

Since 2012, the pair have averaged roughly US$170 billion in annual trade in goods [4], making Germany the US’s fifth-largest trading partner in that time (behind Canada, China, Mexico and Japan).[5] While China surpassed the US as Germany’s largest trading partner in 2017,[6] the US remains Germany’s top foreign market, receiving 8.4% of all German exports.

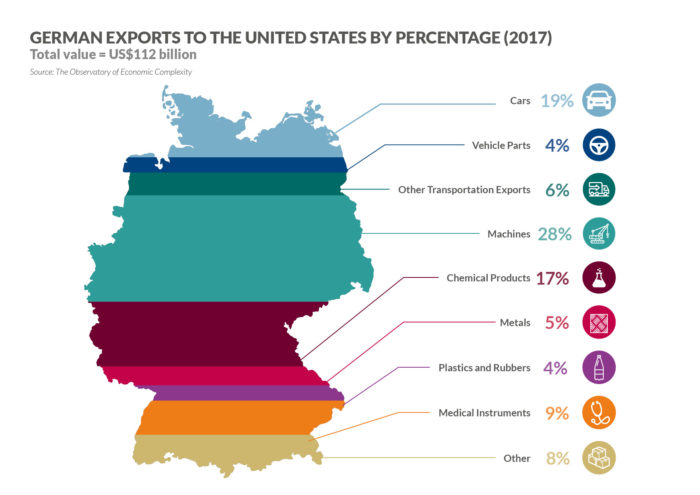

In terms of composition, in 2017, transportation goods accounted for a full 30% of German exports to the US. Cars and car parts are primarily responsible for this, owing to the strong performance in the US of premium German automobile brands such as BMW and Mercedes-Benz.[7] (German-branded automobiles accounted for 8% of total US car sales in 2017, but only about 37% of these cars originated in Germany.[8] The majority of units sold were built in massive plants in the US or neighboring Mexico. See Section IV for more detail.)

Meanwhile, machinery constituted an additional 28% of German exports to the US, a figure that hints at the strong performance of German small- and medium-sized enterprises. These famous Mittelstand firms account for 99% of German companies [9] and produce high-quality intermediate and manufacturing parts that, even if more expensive than competing options, are in demand worldwide.

For US exports to Germany, the portfolio distribution is somewhat similar, with machinery, chemical products and transportation goods accounting for 64% of German imports from the US in 2017. (Those three sectors totaled 75% of US imports from Germany that year). [10]

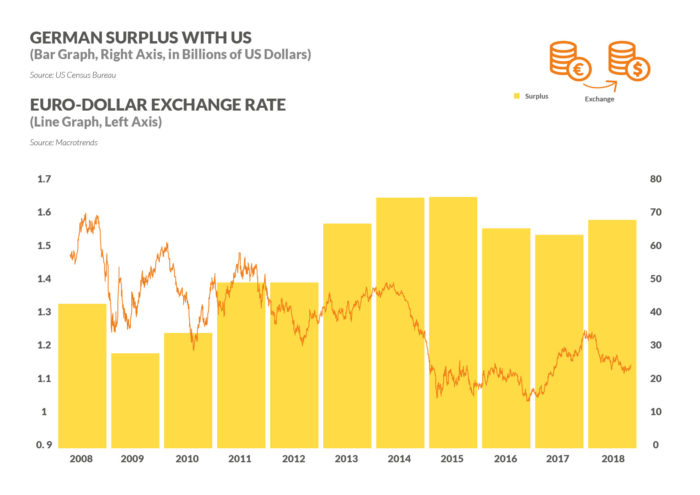

American concerns, however, do not focus on the composition of imports and exports. It’s the discrepancy in value that irks Washington. From 2008 to 2018, Germany averaged a US$57 billion annual trade surplus with the US. Such a figure might not be unexpected since the US maintains the world’s largest overall trade deficit and Germany routinely racks up one of the globe’s largest overall surpluses, one that is, for example, 50% higher than China’s in 2016. [11]

The imbalance has caught President Trump’s ire. “We have a MASSIVE trade deficit with Germany,” he tweeted in May 2017. “Very bad for the U.S. This will change.”

The American trade deficit with Germany is, in fact, the US’s third-largest. [12] Rather than using this statistic to condemn the bilateral trade relationship, however, it’s worth asking why such a deficit exists and the extent to which it evidences a skewed relationship.

What propels the German surplus? Trade hawks have used the figures to insinuate that German export success is built on unfair practices, in part through an advantage from the eurozone’s artificially weak common currency.[13]

To be sure, Germany has benefited from a depreciated euro that props up the competitiveness of its exports. The IMF has estimated “that Germany’s real effective exchange rate is 10 to 20 percent undervalued.”[14] Meanwhile, Germany maintains a large trade surplus with its EU partners — €159.3 billion in 2017 — a self-perpetuating dynamic that helps reinforce the country’s export economy while draining resources from other EU member states.[15]

Still, a depreciated euro may be an unfair scapegoat. After all, Germany is but one member in the 19-country currency union. The European Central Bank’s single mandate is to pursue purchasing power stability; it does not take steps to maintain trade advantages. To the extent that these exist, they are determined by market forces. And while Germany might well tolerate a stronger euro, many other countries in the currency union likely could not. World Economics’ price indexing research has suggested an overvalued euro for Greece, Italy and, most recently, France.[16]

Finally, as economist and former ECB senior manager Marcel Fratzscher has argued, analysts may overemphasize the impact of a cheaper euro when considering trade balances. “Owing to the integration of global value chains, industrial exports now comprise many imported inputs, which means that the effect of exchange-rate movements on domestic prices and the trade balance has decreased substantially over time,” he wrote.[17] In fact, as depicted in Chart 3, the trade deficit has remained relatively consistent, even decreasing slightly, between 2014 and 2018, despite the euro’s nearly 20% depreciation against the US dollar during that period.

Thus, while an undervalued euro (at least in Germany) benefits German exports to the US, the exchange rate does not appear to offer a strong explanation of Berlin’s bilateral trade surplus.

Analysts who view maleficence behind the trade imbalance also point to high EU tariffs on US goods, especially in strategically significant sectors such as agriculture, despite low US tariffs on EU goods. If true, this would violate President Trump’s self-professed favorite tenet, “reciprocity”, and would render the US, in the president’s view, a “sucker country”. “The European Union is possibly as bad as China, just smaller. It’s terrible what they do to us,” he stated in a 2018 interview with Fox News.[18]

In May of that year, Washington began levying tariffs on US$7.7 billion of EU steel and aluminum exports, and the EU retaliated with its own taxes on US goods.[19] The trade skirmish risked developing into war later that year when President Trump threatened to extend the tariffs to EU auto exports, a thinly veiled threat to the German economy. A series of emergency meetings between Trump and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker averted the escalation, but Trump has continued to hold out the threat of potential action, a strategy that EU officials have likened to a loaded gun pointed to their heads.[20]

Is it true that US-EU trade relations are based on unfair terms? President Trump has cited little evidence beyond the burgeoning EU surplus with the US, which, just as in US-German trade, does not necessarily indicate an uneven playing field. Averaged weighted EU tariffs are indeed slightly higher than the US’s,[21] but in both cases they are very low.[22]

As Chart 4 indicates, the slightly higher EU tariffs hold across multiple sectors. But the minor differentiation seems unlikely to account for the trade imbalance, especially considering that non-tariff barriers on goods are essentially equal on both sides of the Atlantic.

President Trump has expressed concern, in particular, about EU duties levied against American automobiles and agricultural produce. In fact, US cars do face a 10% tariff entering the EU while EU exporters pay only a 2.5% tariff to get their automobiles into the US.[23] And for produce, the EU has long protected its farmers with subsidies and tariffs. As Chart 4 demonstrates, the highest EU tariffs are typically associated with agricultural goods.

While these differences may impact the trade relationship at the margins, they are unlikely the root cause of the trade imbalance. In some cases, the different tariff schedules simply reflect strategic industries that countries have chosen to protect over decades of policymaking. US tariffs on cars may only be 2.5%, but it maintains a 25% tariff on trucks. In terms of agriculture, the US itself has recently taken to subsidizing its farmers as a consequence of its trade conflict with China. Moreover, in October 2019 Washington announced increased tariffs on EU agricultural products following a World Trade Organization verdict against Brussels for subsidizing Airbus.

Ironically, when Trump entered office in 2017, he inherited years of US–EU trade negotiations geared towards eliminating the tariff discrepancies he finds distasteful. Yet as part of a broader, wholesale effort to undo any initiative associated with his predecessor, Barack Obama, Trump scuttled Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations on his first full day in office.

III. The Causes of the Imbalance

If neither a depreciated euro nor tariff discrepancies can account for the German-American trade imbalance, what does? In this section, the paper considers why German exports to the US are so high and imports from the US markedly lower.

A. German Competitiveness

Germany can thank its extremely competitive goods for its high export surpluses, whether with the US or elsewhere. This is especially true for niche or high-end markets that do not place German-made products in direct competition with those of other major exporters such as China.

Whereas both Germany and the US are considered to have advanced, western economies, their manufacturing prowess has differed markedly in the 21st century. According to the World Bank, US manufacturing in 2017 accounted for only 11% of value added to domestic GDP. The figure for Germany, 20%, is nearly double and among the highest in the world, alongside that of Asian countries such as South Korea, China, Indonesia and Japan.[24]

Much of this success is attributed to the Mittelstand firms that frequently specialize in automobile or machinery parts that can be sold by the millions worldwide, even if few have heard of the brands. The products’ quality and reputation allow German companies to charge a premium. In addition, these small- and medium-sized firms are frequently family-run, and have union representation on their boards. Financially, they rely on maintaining relationships with banks as opposed to capital markets. These factors have facilitated long-term strategies, as opposed to short-sighted cash grabs that may please shareholders.[25]

The success of these companies is stunning, especially in an era when manufacturers are exiting the developed world. Businessman and economist Hermann Simon found 2,734 firms worldwide that: a) were among the top three in their industry globally; b) had annual revenue below €5 billion; and c) were generally unknown to the public. Forty-seven percent of them are German.[26]

Should the US try to emulate the Mittelstand’s success? Or is American manufacturing decline a harbinger for Germany? The US could pursue the vocational training and apprenticeship programs that have been key to developing Germany’s skilled manufacturing capacity. However, some economists argue such an effort would be misguided. Advances in technology and automation could soon doom manufacturing jobs that require skilled workers, either by eliminating those positions or making them transportable to countries with lower labor costs.[27]

Another reason for caution may be the German economy’s flirtation with recession since 2018, a malaise driven by declining manufacturing output. Long-term structural issues, however, do not appear to be the root cause of the slump. Rather, Germany has incurred collateral damage stemming from the recent US trade conflict with China and the prolonged saga of Brexit. Both factors underscore the risks of an export-led economic model, but they do not, as of yet, portend the end of German competitiveness in global trade.

B. A Propensity to Save

The fundamental issue driving Germany’s trade surplus with the US is the two countries’ different propensities to save. By reorganizing the basic equations of gross domestic product, we see that net exports equals a country’s savings minus investment. Thus, a country that runs up a significant trade surplus must be saving far more than it is investing.

In Germany, the predilection to save ranges from consumers “who are stashing cash in mattresses and checking accounts [to] the state, which has run a budget surplus for five years, [to] companies, which are hoarding profits”.[28]

Explanations for the desire to save vary. Some sources highlight an ingrained “German frugality”,[29] while others site a longstanding collaborative effort between German employees and unions to restrain wage growth.[30] The dynamic is compounded by demographic trends. As Germans age, they are more inclined to save for retirement. All told, German consumption hit 54% of GDP in 2017, considerably less than the 69% of GDP in the US.[31]

The fact that Germans prefer to save is by no means evidence of the type of maleficence or cheating that the President Trump administration has alleged. Whether it’s the state, the business sector or individuals, Germans have the right to spend — or not spend — their money as they see fit. Their American counterparts, saddled with massive public and private debt, are in no position to lecture on fiscal strategies, even if looser German purse strings would likely result in increased American imports.

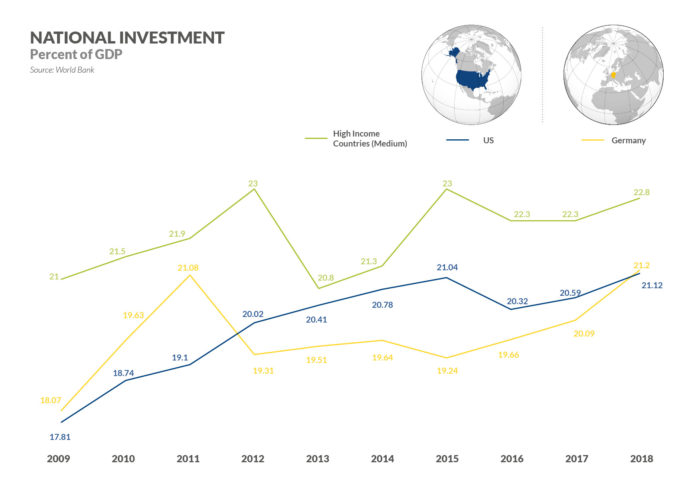

That said, a strong argument can be made that Germany could benefit from increased spending. German savings could be redirected towards investment to boost infrastructure capacity, whether physical, digital or human. Analysts suggest the quality of German roads, bridges and airports are feeling the stress of neglect.[32] Underinvestment in technological development leaves Germany behind in the race to develop artificial intelligence.[33] And the country’s schools require important upgrades to prepare the next generation for the 21st-century economy.

Both current German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz and his predecessor, Wolfgang Schäuble, claim that the government has earmarked chunks of its budgetary surplus for investment, but that project implementation frequently gets caught in bottlenecks, perhaps related to longstanding norms in disposition.[34] Scholz told the Financial Times in late 2019 that unused public funds earmarked for investment stood at €15 billion, around 4% of the federal budget.[35]

Given the very low cost of cash — the ECB’s negligible central bank rates are another of President Trump’s bugaboos — Germany could be missing an advantageous window to pursue large-scale investment projects. Such spending would also, to some degree, result in increased imports from the US.

Still, the US is also ill-positioned to critique German investment levels. As Chart 6 demonstrates, the US has only slightly outpaced Germany in terms of national investment over the last decade, and both countries consistently fall below the median pace for high-income countries.

IV. Foreign Direct Investment

Twenty-first-century economic relationships are, of course, about more than direct trade of physical goods, especially between countries as large and intertwined as Germany and the US. Another critical factor to consider in the broader relationship, including the German trade surplus, is foreign direct investment (FDI).

The previous section elaborated on German domestic underinvestment. It’s a different story for German investment abroad. In fact, Germany is the source of 8% of FDI in the US over the last decade.[36] Moreover, 38% of that FDI is in the industrial sector, which offers job-creation opportunities.37 The German Times reports that German companies employ 674,000 people in the US.[38]

German auto manufacturers in particular have set up massive bases in the US. President Trump has cited the number of German cars in the country as evidence of skewed trade, but in 2017 only about 35% of the 1.35 million German vehicles sold in the US were imported from Germany.[39] Most of the remainder were built in the US (some were also built in Mexico). BMW, Volkswagen and Mercedes-Benz have large plants across the American South, and their production has increased nearly fivefold since 2013.[40]

This increased presence reflects two important insights into the US-German relationship. First, German producers play a valuable role in generating employment. Chart 8 displays the employment impact of German affiliates by state. Second, this kind of FDI, which the Trump administration encourages,[41] requires German imports. German cars are produced with German parts, or at least parts that were first imported to Germany. Thus, the increasing activities of German affiliates, which creates US jobs, also contributes to the German trade surplus.

President Trump’s trade tactics threaten the ability of these US-based German affiliates to operate. New tariffs can impact their ability to import materials for production. The tactics could also worsen the US trade balance. Since a non-negligible portion of the German cars built in the US are exported to China,[42] a Sino-American trade war would negatively impact German affiliates’ American exports. All this would make the US a less attractive destination for FDI.

Although the US is the largest source of FDI in Germany, here, too, dangers lurk. Populist forces have already cast a shadow over the relationship. Brexit-related uncertainty has generated an overall decline in FDI into Germany as potential investors are unsure about the access a German base will have to the UK market.[43]

According to a KPMG study, US FDI to Germany faces an additional challenge from an underdeveloped digital infrastructure.[44] Germany has the world’s fifth-largest ICT (information and communications technology) economy and Europe’s largest software market, with nearly 90,000 IT companies.45 Nevertheless, only 16% of German firms use cloud services.[46] A 2017 OECD report ranked Germany 29th among 34 industrialized economies in terms of internet speed, a concern for digitally oriented American firms.

This digital underdevelopment could be an area ripe for US investment, and major US firms such as Google and Amazon have announced initiatives based in Germany. But the country maintains a healthy skepticism of FDI in its AI sectors. In late 2019, Economy Minister Peter Altmaier announced greater restrictions on international investment in German high-tech firms. The move was primarily aimed at China, which has increasingly sought stakes in German AI and robotics[47], but it hints at a broader disposition that FDI in German tech represents a security or privacy vulnerability.

Do bilateral trade balances matter?

As US policymakers reflect on the American trade deficit with the EU, particularly with Germany, a debate on the benefits and drawbacks of this state of affairs has emerged. But focusing only on a bilateral trading relationship can be misleading. Most advanced economies feature a series of bilateral deficits with some counties and surpluses with others.

For a comparison, consider an individual’s personal finances. An Uber customer, for example, has a bilateral deficit with the company. The rider typically accepts that arrangement because the deficit is (hopefully) more than covered by a surplus (i.e., in- come) from their employer. If bilateral deficits are malign, the rider could eliminate it by becoming an Uber driver until paid the exact amount spent on rides. This is deeply inefficient, however, especially if the customer tried to balance trade in all bilateral relationships, such as those with the grocery store and the gas station.

The logic also applies to countries. Brazil maintains a trade surplus with China and a deficit with the US. But this alone indicates neither that Brazil is exploiting China nor that the US is taking advantage of Brazil.

Overall trade conditions are of more analytical value. An individual who trades at a deficit with Uber, the grocery store and the gas station without a surplus elsewhere faces financial problems. The US maintains a global deficit in trade, while Germany has an overall surplus. But without further con- text, tallying the pair’s particular bilateral surplus or deficit can be less telling than some might think.

V. Economics in a Time of Nationalism

The German–American economic relationship will remain robust and mutually advantageous in the near term. Nevertheless, both sides could take strategic steps that would benefit their domestic economies and tighten economic ties. This paper has shared arguments for increased German domestic investment. Coupled with increased consumption, this could yield a boost in US imports that would help close the American trade deficit.

Discrepancies do exist in the US and EU tariff schedules, but this could be addressed by reinvigorating dialogue on a TTIP. Efforts for such a pact were mutually unpopular before, but the geopolitical benefit of such an agreement appears to have been poorly understood in Berlin, Washington and other capitals.

Those who knocked the potential of such a deal feared that it would undermine labor, health and product standards. But US and EU norms in these areas are significantly more robust than those of a number of emerging-market trading powers, most glaringly China. A US-EU pact would permit them to heavily influence the rules of the game for a 21st-century trading regime while addressing the lingering differences in the existing tariff schedules.

President Trump continues to threaten significant tariff increases on strategically important German exports such as automobiles. He is, however, unlikely to follow through on such threats in 2020. The president views stock market performance as vital to his reelection, and equities have responded distinctly negatively to his quixotic tariffs and trade conflicts.

On the contrary, 2020 may offer opportunities to put the trade conflict in the rear-view mirror. If the EU can offer the Trump administration concessions, the president may be inclined to accept them, claim victory and ease off existing tariffs and tariff threats. This would provide a positive jolt to the stock market, an advantage to a presidential incumbent in an election year.

There is greater uncertainty in the long term. In two decades, Germany has gone from being “the sick man of Europe”[48] to boasting one of the world’s strongest economies. The country has accomplished this by embracing globalization. It has also successfully leveraged an industrial sector with comparative advantages in capital goods, and luxury and niche manufacturing.

A global trend towards economic nationalism threatens Germany’s ability to continue executing that strategy. Given the importance of Anglo-German trade, Brexit is one manifestation of the threat. Another is the friction in Sino-American trade, which hits Germany’s exports to China, the largest market for German goods. A third is increased American tariffs and the possibility of further such action specifically tailored to hurt the German economy.

A collapse of the German economic model could lead the EU as a whole to pursue its own inward-looking, nationalist economic policy. Jeromin Zettelmeyer of the Peterson Institute for International Economics argues that Germany’s new National Industrial Strategy for 2030 is already a step in this direction, with its argument for developing domes- tic champions, even at the expense of competitiveness, and its promotion of EU supply chains.[49] As German and French politicians push for increased economic EU nationalism, the illiberal trends that have circled the globe could seep into Europe’s core. That could reorient the German–American economic relationship, sparing neither trade nor FDI.

In the decades following World War II, the two countries’ partnership blossomed from a mutual commitment to a post-war liberal order based on open markets and liberal democracy. In recent years those foundational pillars have come under increasing pressure. How the US and Germany react to the current liberal slump will frame their future economic relationship.

Sources:

[^1]: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/coun- tries/united-states/

- Susan Glasser. “How Trump Made War on Angela Merkel and Europe.” The New Yorker, December 17, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/12/24/how-trump- made-war-on-angela-merkel-and-europe

- While trade in services is a sizeable and relevant element of the US–German economic relationship, this trade is generally even, and is conducted under generally comparative tariffs and terms, and thus is not directly considered in this text.

- US Census. (https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c4280.html)

- US Census. https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/highlights/top/top1212yr. html

- “China overtakes US and France as Germany’s biggest trading partner.” Reuters, Fe- bruary 24, 2017. https://www.cnbc.com/2017/02/24/china-overtakes-us-and-fran- ce-as-germanys-biggest-trading-partner.html

- The Observatory of Economic Complexity. https://oec.world/en/visualize/tree_map/ hs92/export/deu/usa/show/2017/

- Charles Riley. “Made in America: The German cars Trump doesn’t want.” CNN Bu- siness, June 12, 2018. https://money.cnn.com/2018/06/11/news/economy/german-cars- trump-trade/index.html

- Caroline Bayley. “Germany’s ‘hidden champions’ of the Mittelstand.” BBC News. Au- gust 17, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-40796571

- The Observatory of Economic Complexity.

- “Why Germany’s current-account surplus is bad for the world economy.” The Econo- mist, July 8, 2017.

- “US Trade Deficit by Country, 2020. ”World Population Review, 2020. http://worldpo- pulationreview.com/countries/us-trade-deficit-by-country/

- Jamie McGeever. “Euro may be too weak for Germany but too strong for others.” Re- uters, February 3, 2017.

- Frances Burwell. “German trade surplus with US far more complex than Trump makes it.” The Hill, July 18, 2017. https://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/economy-budge- t/342538-german-trade-surplus-far-more-complex-than-trump-makes-it

- Michael Ivanovitch. “Germany’s huge trade surpluses are a burden on its EU partners.” CNBC, August 6, 2018.

- “France and the Euro – The Real Reason for the Riots?” World Economics, July 2019. https://www.worldeconomics.com/WorldPriceIndex/WorldPriceIndex-Spotlight.aspx

- Marcel Fratzscher. “How to understand Germany’s trade surplus: is it exploiting the weak euro?” Euronews, July 3, 2017. https://www.euronews.com/2017/03/07/view-how- to-understand-germany-s-trade-surplus

- Carolina Houck. “Trump calls Europe ‘as bad as China’ on trade.” Vox, July 1, 2018. https://www.vox.com/world/2018/7/1/17522984/europe-china-trade-war-trump

- Mark Landler and Ana Swanson. “U.S. and Europe Outline Deal to Ease Trade Feud.” The New York Times, July 25, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/25/us/politics/ trump-europe-trade.html

- Lionel Laurent. “Donald Trump Still Has Germany and the EU in His Sights.” The Washington Post, May 16, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/donald- trump-still-has-germany-and-the-eu-in-his-sights/2019/05/16/51fc8bca-77ad-11e9- a7bf-c8a43b84ee31_story.html

- Raoul Leering and Timme Spakman. “Unfair trade: Does President Trump have a point?” ING Economic and Financial Analysis. April 4, 2018. https://think.ing.com/arti- cles/unfair-trade-does-president-trump-have-a-point/

- Lauren Chadwick and Darren McCaffrey. “Is the US right to claim the EU is not treating it fairly on trade?” Euronews, July 26, 2017. https://www.euronews.com/2019/06/05/is- the-us-right-to-claim-the-eu-is-not-treating-it-fairly-on-trade

- Marianne Schneider-Petsinger. “US–EU Trade Relations in the Trump Era Which Way Forward?” Chatham House, March 2019. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/ files/publications/research/2019-03-08US-EUTradeRelations2.pdf

- Word Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.ZS?end=2018&loca- tions=US-DE&start=1960&view=chart

- John Ydstie. “How Germany Wins At Manufacturing — For Now.” National Public Ra- dio, January 3, 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/01/03/572901119/how-germany-wins- at-manufacturing-for-now

- Hermann Simon. “Why Germany Still Has So Many Middle-Class Manufacturing Jobs.” Harvard Business Review. May 2, 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/05/why-germany- still-has-so-many-middle-class-manufacturing-jobs

- See comments from the Brooking Institution’s Martin Baily in Ydstie.

- Tom Fairless and Patricia Kowsmann. “Germans Keep on Saving Their Money—Even When It Hurts.” The Wall Street Journal, December 3, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/arti- cles/germans-keep-on-saving-their-moneyeven-when-it-hurts-11575388824

- Ibid.

- “Germany’s current-account surplus is a problem.” The Economist, February 11, 2017. https://www.economist.com/europe/2017/02/11/germanys-current-account-sur- plus-is-a-problem

- “Why Germany’s current-account surplus is bad for the world economy.” The Econo- mist, July 8, 2017.

- Ben Bernanke. “Germany’s Trade Surplus is a Problem.” Brookings Institution, April 3, 2015. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-bernanke/2015/04/03/germanys-tra- de-surplus-is-a-problem/

- Janosch Delcker. “Germany’s falling behind on tech, and Merkel knows it.” Politico, July 23, 2018. https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-falling-behind-china-on-tech-in- novation-artificial-intelligence-angela-merkel-knows-it/

- Ibid

- St

- Stormy-Annika Mildner. “German and US companies are among the most important foreign investors in each other’s markets. A trade war is bad for everyone.” The German Times, October 2018. http://www.german-times.com/german-and-us-companies-are- among-the-most-important-foreign-investors-in-each-others-markets-a-trade- war-is-bad-for-everyone/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Riley.

- Ibid.

- For example, see Jack Ewing and Ana Swanson. “Trump May Punt on Auto Tariffs as European Carmakers Propose Plan.” The New York Times, November 11, 2019, https:// www.nytimes.com/2019/11/11/business/trump-auto-tariffs.html

- Brian Hanrahan. “Will Trump’s tariffs really hurt German carmakers?” Han- delsblatt Today, March 17, 2018. https://www.handelsblatt.com/today/its-compli- cated-will-trumps-tariffs-really-hurt-german-carmakers/23581508.html?ticke- t=ST-139993-OIyq5xjYmYuDgMeBpOgO-ap4

- Timothy Rooks. “US businesses less willing to invest in Germany.” DW News, Decem- ber 2, 2019. https://www.dw.com/en/us-businesses-less-willing-to-invest-in-ger- many/a-51499249

- Ibid.

- Export.gov, “Germany – Information Technology.” From the Germany Country Com- mercial Guide, accessed October 28, 2019.

- The OECD average is 25%, and 57% of firms in Finland use cloud computing services. Paul Carrel, “Where Europe’s most powerful economy is falling behind.” Reuters, June 25, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/germany-digital-gap/

- Christian Kraemer and Madeline Chambers. “Germany to tighten foreign investment rules for critical sectors.” Reuters, November 28, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/ us-germany-m-a-foreign/germany-to-tighten-foreign-investment-rules-for-criti- cal-sectors-idUSKBN1Y21W4

- “The sick man of the euro.” The Economist, June 3, 1999. https://www.economist. com/special/1999/06/03/the-sick-man-of-the-euro

- Jeromin Zettelmeyer. “The Troubling Rise of Economic Nationalism in the European Union.” The Peterson Institute for International Economics, March 29, 2019. https:// www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/troubling-rise-economic-na- tionalism-european-union