Democracy

Pictures Worth a Thousand Policies: Campaign Imagery from Bavaria’s State Election

On October 8, 2023, Bavaria hosted its state election. Ranked second in gross regional product and population, Bavaria has always had a sizable influence on German politics, with many seeing this year’s state election as a bellwether for what to expect at the national level in 2025.

Despite its political sway, campaigns in the state are almost impossible to duplicate elsewhere in Germany. “Beer tent speeches” that run the gamut from informative and approachable sit-downs to boisterous, borderline-populist rallies are a staple. Candidates use them to make inroads with the Bavarian electorate by putting distance between themselves and the oft maligned “Berlin bubble.”

However, the day before the election, politics were not happening in the beer tents, but rather under pop-up canopies that served as part promotion, part rain protection, during a damp afternoon on Munich’s Marienplatz. With the city’s iconic courthouse and whimsical Glockenspiel in the background, candidates and volunteers fought through the tourist hordes to engage voters before they hit the polls. Five of the major contenders spread out across the cobblestones, with several smaller parties off to the side. Conveniently organized on the square according to their place on the political spectrum, the Left Party, the Green Party, the center-left Social Democrats (SPD), the neoliberal Free Democrats (FDP) and the conservative Free Voters handed out fliers and other promotional materials in a final effort to sway voters. Offering the standard postcards and pamphlets, and more unusual items such as packs of tissues, bumper stickers and totes, each party deployed messaging strategies meant to appeal to their bases and, perhaps more importantly, to the undecided. Noticeably absent was the perennial favorite, the conservative Christian Social Union (CSU), and the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD). The AfD had canceled two rallies earlier that week in Bavaria, citing security concerns and an alleged "violent incident."

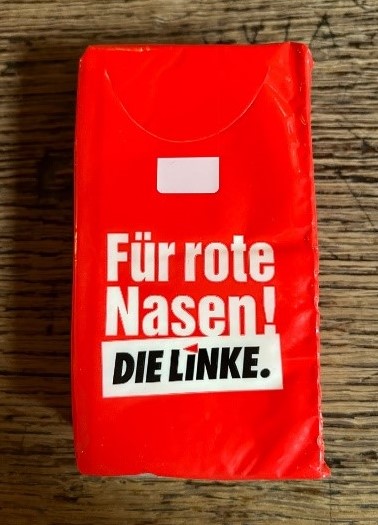

The Left Party branded itself as “Bavaria’s Opposition” on the campaign poster hanging in its information booth. The pamphlet laying out the party’s platform highlighted four issues: affordable rent, education, competitive wages, and a consistent and socially just climate policy. Volunteers also distributed packs of tissues designated “for red noses,” a play on the Left Party’s signature color.

The Green Party had a colorful stand with several pamphlets, explaining its platform in detail as well as in an abridged version featuring, on the cover, a smiling emoji surrounded by hearts. It was titled “Three Reasons for Green!” Another handout, referring to the party colors of the current national governing coalition of Greens, SPD (red) and FDP (yellow), highlighted “Green Successes in the Traffic Light Coalition.” The pamphlets were weighed down with painted rocks, which sparked conversations at the booth about a rock thrown at the state party’s lead candidates Katharina Schulze and Ludwig Hartmann during a campaign event in September. Major issues for the Greens included consistent climate policy, economic growth, climate-friendly mobility, environmental protections, affordable cost of living and education.

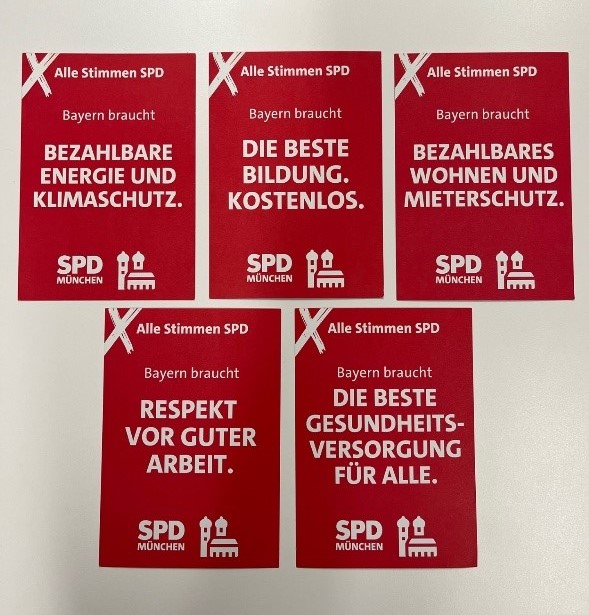

The SPD distilled its party platform down to five campaign issues—affordable energy and climate protection, affordable living and renter protection, free education, universal health care and respect for good work. Spread across the table, red postcards highlighted each of these issues under the heading “Bavaria needs.” The postcards’ flip sides offered policy proposals, often in direct opposition of those pursued by the ruling CSU-led government. To drive the point home, party representatives distributed stickers with the face of Bavarian Premier Markus Söder and the tagline “Söder? Nein Danke,” a replay of the slogan of the anti-nuclear movement in the 1970s.

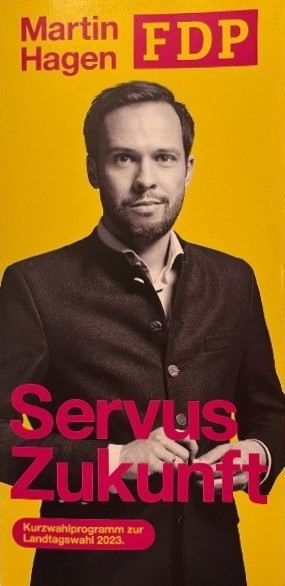

Compared to its federal government coalition partners, the FDP had a smaller presence. Its representatives distributed highly stylized pamphlets titled “Hello Future." The text outlined a wide-ranging platform on bureaucratic efficiency, migration policy, climate change, affordable rent and faster internet. It also called for a “Liberalitas Bavariae,” a movement that has evolved to be synonymous with personal freedom. For the FDP, this was pushback against prior COVID-19 restrictions and support for domestic security through a “well-appointed police and judiciary” rather than a “nanny state.”

The Free Voters had a steady stream of visitors throughout the afternoon and distributed more promotional material than any other party present. It was packaged neatly in bright orange totes that could be seen throughout the city later that day. The Free Voters offered five priorities as part of their platform: homeland (Heimat)/agriculture, society/security, economy/energy, education and family/social issues. For Heimat, the party’s priority was “to promote culture and customs, keeping tradition.”

Although not present on Marienplatz that day, the CSU put up several large campaign posters nearby. One focused on the cost of living, affirming that “Munich must be affordable.” The other, plastered on an eight-foot-tall column, featured a headshot of Söder above the slogan “So that Bavaria remains strong and stable.”

For all parties except the Free Voters, their efforts on Saturday served little purpose for Sunday’s vote. And the CSU and AfD were right not to attend; they did not have to. The CSU won 37% of the vote, a historic second-worst performance but nonetheless a significant showing. The Free Voters followed with 15.8%, a 4-percentage-point improvement over the previous election in 2018 despite allegations that party leader Hubert Aiwanger authored an antisemitic flyer as a teen. He denied doing so. But Aiwanger did lean into the controversy amid calls for his resignation, and he derided the scandal as an example of cancel culture and dirty campaign tactics. The strategy clearly worked, and he will remain Bavaria’s deputy premier. The AfD came in third, with 14.6%, reflecting the largest gain (4.4 percentage points) for any party since the previous state election.

If Bavarian beer tents are a response to Berlin’s bubble, the dissatisfaction was evident in the election results. The state branches of all three parties in power in Berlin lost ground. The FDP did not even cross the 5% threshold needed to remain in the Bavarian parliament. Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s SPD slipped marginally, from 9.7% in 2018 to 8.4% in 2023. The Greens, coming off a historic showing of 17.6% in the previous election, garnered a still-respectable if reduced 14.4%. The party won four districts outright compared to the CSU’s 85 and the Free Voters’ two. The Left Party, always at odds with Bavaria’s more conservative electorate, continued its journey into oblivion by losing more than half its voters to garner just 1.5%.

Bavaria’s election results were largely as predicted, leaving little room for surprise. It was nevertheless interesting to see the state parties’ various branding and the differences between the national and state party platforms. Consensus building on regional issues, such as affordable rent and sufficient daycare, may now be the basis for cooperation in the reestablished CSU-Free Voters state government. It may even provide best practices for the national administration, taking them from the beer tent to the bubble.